20/05/2021

During the 1950’s Cabo Blanco was considered the world’s sport fishing mecca. Three ocean currents met right in front of its shores: the cold Humboldt, the warm-watered El Niño, and the Cromwell undertow pushing sea nutrients to surface, luring as much as 70% of Peru’s marine diversity into these tropical waters. In August 1953, Louisiana oilman Alfred Glassell Jr. landed the all-tackle world record in game fishing in Cabo Blanco catching a 1560-lb black marlin (Makaira indica), whilst another game fish world record also surfaced from the Cabo Blanco waters – the famous 435-lb Bigeye Tuna (Thunnus obesus) caught in 1957. Movie stars from Hollywood’s golden days used to spend summer in Cabo Blanco, and Nobel-Prize Laureate Ernest Hemingway rode the iconic ‘Miss Texas’ boat throughout April 1956 trying to beat Glassell’s milestone.

Over time, the overexploitation of resources has endangered Cabo Blanco’s sea life. Contributing to the conservation of one of the world’s most precious marine ecosystems, since 2012 Inkaterra Asociación proposes the creation of Peru’s first-ever marine reserve in Cabo Blanco’s Tropical Pacific. In alignment with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, the initiative aims to restore the cycle of life in the marine coastal desert of Cabo Blanco, championing ecotourism and millenary artisanal fishing (declared a cultural patrimony of Peru back in 2018).

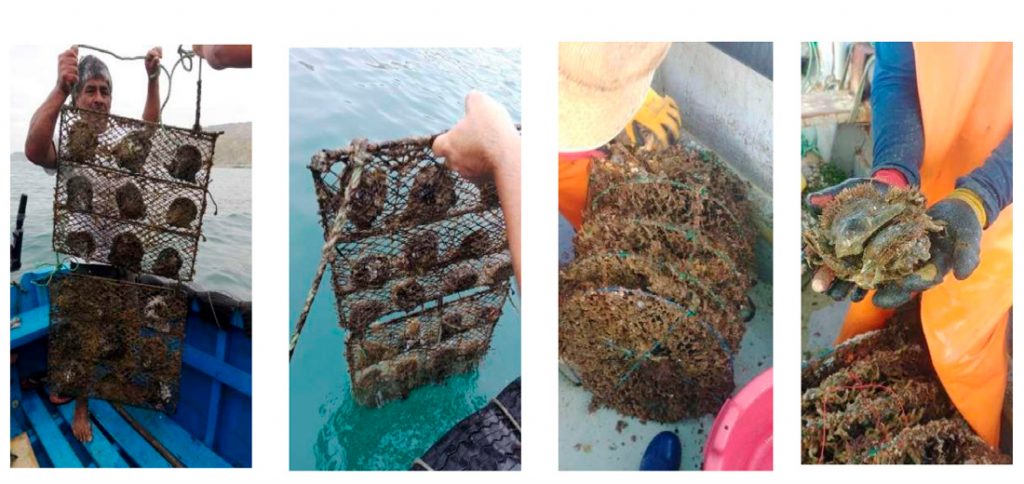

However, the resistance imposed by certain industrial activities has delayed a measure as urgent as the official declaration of a marine reserve for Peru. In an effort to find innovative ways to preserve the Peruvian Tropical Pacific, NGO Inkaterra Asociación, in alliance with the National Fishing and Aquaculture Innovation Program (PNIPA), AGROMAR, and the Cabo Blanco Artisanal Fishing Association, managed to establish a 100-hectare marine concession – a safe haven protecting marine diversity against illegal fishing and other predatory practices.

This strategic partnership primarily employs the concession for the sustainable harvesting of the rainbow-lipped Pearl oyster (Pteria sterna), a bivalve mollusk species from the Pteriidae family, with a distribution range comprehending the shallow waters of the Tropical Pacific, from Baja California to Northern Peru. A sustainable source of development for the local fishing communities of Cabo Blanco and their families, as women are mainly involved in this pilot program.

“For the past four decades we have witnessed how the coastal communities in Baja California, Mexico, have benefitted from pearl harvesting as one of the mains sources of development through sustainable jewelry and nacre-derived products,” explains the project’s general coordinator Jorge Vargas. A representative of master scallop producer Fernando Fernandini, leader of Agromar, Vargas finds an extraordinary potential in this way of entrepreneurship new to the Cabo Blanco community. “In Mexico, a pearl-derived jewel coated in silver may cost around $150, while $300 if encrusted in gold. Some jewelry is priced up to $2000, evidencing the potential for development in coastal communities such as Cabo Blanco.”

Training workshops for the Cabo Blanco artisanal fishing community and their families, teaching sustainable methods for pearl harvesting with an approach to marine conservation. Dr. Mario Monteforte, Mexican biologist who led the lessons on perliculture, was in awe with the bright future envisioned for this activity in Northern Peru.

Though the COVID-19 pandemic has brought pearl harvesting to a halt, the community is eager to resume operations and keep exploring an activity with such a potential for experiential travel and jewelry, in a destination where the abundance of prime material is ten times larger than in Baja California.

Initiatives on responsible pearl jewelry are already being developed in Cabo Blanco. Such is the case of Katerina Norgaard’s Usiyanya (“sea” in Quechua), a jewelry collection inspired by Peruvian heritage and the Pacific Ocean. “The collection uses parts of sustainably harvested mother of pearl shells and is constructed in conjunction with artisan women in Cabo Blanco,” states Katerina. “This jewelry collection also aims at supporting the local community in Cabo Blanco – especially woman who are unemployed or dependent – by paying them a fair wage for each piece made. The collection is more than just jewelry, rather it is a project which strives for social change and environmental good, which hopes to inspire future projects through its sustainability and its pursuit of economic justice and authenticity.”

VISIT THE USINYANYA PROJECT HERE:

https://sites.google.com/newschool.edu/sce-katerina-nordgaard/